Paul Brundsaux, legend of the French Foreign Legion

Javier Gómez Valero

1898 Miniaturas

A vertiginous military career marked by campaigns in such distant confines as Tonkin, Dahomey, Madagascar or the Sahara, a courage worthy of the Légion d’honneur in three categories and an overwhelming personality marked the life of Paul Brundsaux, iconic character of the French Foreign Legion.

Four statues guard the memorial to the fallen of the 1st Regiment of the Foreign Legion erected in 1931 at the corps’ mythical Algerian base in Sidi bel Abbès, and moved to Aubagne, France, in 1961. Each one honors the legionnaires of four different periods: 1830-1840 (including the baptism of fire of the Legion, in the First Carlist War), the Mexican campaign, the colonial conquests of 1885-1910 and the First World War. The third of them, corresponding to what we can consider the golden age of the Legion, bears the face (and the exuberant two-pointed beard) of one of its heroes, Paul Brundsaux.

Paul Brundsaux as a senior officer of the Foreign Legion, with the Légion d’honneur and various medals from his campaigns on his chest.

Born in 1855 in the Lorraine town of Beaumont, in the Vosges, into a wealthy family (his father was a doctor), Brundsaux had an imposing physique, slender, 1.80 m tall, gray eyes and brown hair. He entered the 59th promotion (1874-1876) of the Saint Cyr military academy, known as the Grande Promotion due to the spectacular increase in the number of cadets, which in the heat of revenge after the Franco-Prussian War rose from 250 of the imperial age to 406, and which would end up giving France a profitable harvest: one marshal, three corps commanders, four division generals, and twenty-two brigadier generals, including Brundsaux himself.

After graduating from Saint Cyr, he joined the Metropolitan Army, in which he passed through several regiments before arriving in Tunisia. In his memoirs, General Tahon recounts an incident that would mark his career, and that shows his character:

“Brundsaux was a lieutenant in the 4th Zouaves in Tunis when he met a young singer at a café concert. Enthusiastic as he was, he gave himself over to his conquest, and for a few months led a merry life. But one day, having been told by his lover that she was pregnant, he had no doubt that he was the real father and, despite the advice of his colonel and the pleas of his father, who had come to Tunis, he wanted at all costs marry the expectant mother. Denied authorization to marry, he resigned [from the Army] to freely marry the mother of his daughter”.

Paul Brundsaux in the French Foreign Legion

However, the volcanic Brundsaux was not cut out for civilian life and just a few months later, in July 1888, he enlisted in the 2nd Regiment of the Foreign Legion, under a foreign title. Shortly after, he and his family will leave for Tonkin, a destination that has always been highly attractive among recruits because of the exotic nature of the country and, especially, because of the fame of Vietnamese women. The soldier’s experience would begin with a five-week steamship journey that, departing from Marseille, would stop at Oran (where the Legion’s troops were embarked) and, after crossing the Suez Canal, in Colombo and Singapore before arriving to its final destination, Hai Phong, in the Red River delta. After a first contact with Vietnamese culture (particularly with chum-chum, a sickening rice liquor), the newcomers soon found themselves immersed in a harsh guerrilla war in the suffocating climate of the jungles and mountains of Southeast Asia, where fevers and malaria would take a heavy toll. Brundsaux remained there from 1889 to 1891, where he rose to the rank of lieutenant.

After a brief stay in Algeria, in 1893 he set out again to participate in the conquest of Dahomey (present-day Benin), where the Fon people, once preyed upon by the Yoruba slavers, had established a powerful kingdom. The “Prussia of West Africa” owed its might to its strong organization and militarization, which allowed its kings to raise armies of 12,000 fighters, many of them “regulars” armed with firearms obtained from Europeans through trade with human beings. Despite arriving with reinforcements in the final phase of the campaign, when the battle-hardened Fon fighters with terrifying machetes had already been largely subdued, the testimonies of the time attest to the exhausting marches and the constant deaths from disease (casualties among the legionnaires reached at least 75%); of the ferocity of the enemy, especially the famous “Dahomey Amazons”, warrior women who, armed with Spencer carbines and repeating Winchesters and sharp hoes, and naked except for a short skirt (which their officers decorated with a human jaw set in silver over the crotch), they fought like demons to the death; and the cruelty of its rites, especially the human sacrifices whose remains adorned temples and the royal palace itself, whose imposing and gloomy gates were built with skulls. After Dahomey, Brundsaux will be made chevalier of the Légion d’honneur and promoted to captain.

Combat at Dgébé, Dahomey, October 4, 1892, color lithograph in Imagerie d’Epinal No. 190. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1895 he will leave again to participate in the first campaign in Madagascar, where he will distinguish himself during the ordeal that the advance on Antananarivo became, 200 km of terrain bordering on the impassable that would coin the famous expression “march or die”, during which many soldiers fell from sheer exhaustion or blew their brains out to end their misery. The almost zero opposition from the enemy is attested by the insignificant casualties due to combat, only 13 dead and 88 wounded… compared to almost 4,500 deaths from exhaustion and disease, a scandalous 30% of the total troops. In this campaign Paul Brundsaux was promoted to chef de bataillon of the 1st Étranger.

His dizzying progression through the ranks (after starting from scratch in the Legion, he had already caught up with his classmates) was not a hindrance to his explosive personality. After fighting a duel with a comrade on board the ship that brought them back from Madagascar, back in Oran he dedicated himself to living the high life, attending café concerts together with other young officers, forcing the orchestras to play the Legion marching songs under threats and starring in various altercations. Around this time, according to Tahon, “he abandoned his wife and daughter to mix with a black woman.”

In 1900 he will participate in the operations around the Saharan oases of Sud-Oranais, on the blurred border between Algeria and Morocco south of the Atlas. The occupation of the Touat oasis complex, in theoretically Algerian territory but under the spiritual sovereignty of the Sultan of Morocco, aroused anger among the most fundamentalist sectors of the neighboring country, who, faced with the inaction of Fez, launched constant incursions from the Tafilalet oases. Swift attacks of fickle mounted harkas, summer storms that took as little time to form as to dissolve; fortified ksars surrounded by authentic Gardens of Eden in the middle of the most desolate desert; holy wars and cunning warlords eager to demonstrate their baraka… this will be the new theater of operations in which Brundsaux will have to serve.

“In the Sud-Oranais. A reconnaissance of French troops in Moroccan territory”, in Le Petit Jornal no. 839, December 1906.

To consolidate the French advance in the region, the gateway to the desired conquest of the Sahara, strengthened by the construction of a railway, a column was sent to the remote enclave of Igli under the command of Colonel Bertrand, made up of a battalion of “Turks ” of the 2nd Regiment of Tirailleurs Algeriens, the V/1st Étranger de Brundsaux, the 1st Company (Mounted) of the 2nd Étranger, half-squadrons of Spahis and Chasseurs d’Afrique, a section of mountain guns, detachments of sappers and the essential goumiers and meharistes. In total, 2,000 men and 2,000 camels who would suffer equally in this inhospitable environment, like Tonkin or Madagascar, much more lethal to Europeans than enemy bullets. Conditions were so dire that supply columns sent to Igli could lose as many as 50-60 camels a day (an estimated 9,000 between March and November of that year, and a staggering 60,000 animals killed between 1900-1903, an irreparable disaster for the local economy). For these actions in the Sud-Oranais Bundsaux he was made an officier of the Légion d’honneur in 1901.

After serving again in Madagascar, at the end of 1903 Lieutenant Colonel Brundsaux joined the 12th Line Regiment, where he served for two years before rejoining the 1st Étranger, at the head of which he went back to Tonkin, to operate between 1906 and 1908 in the Viet Tri region, where he will once again display his imperturbable gallantry under enemy fire. After this last campaign, he decided to leave the Foreign Legion to return to the Metropolitan Army with the rank of colonel, where he would remain until his final retirement, for health reasons, in July 1916, on the Western Front of the First World War. By then he was a brigadier general and commandeur of the Légion d’honneur. Paul Brundsaux passed away on January 2, 1930.

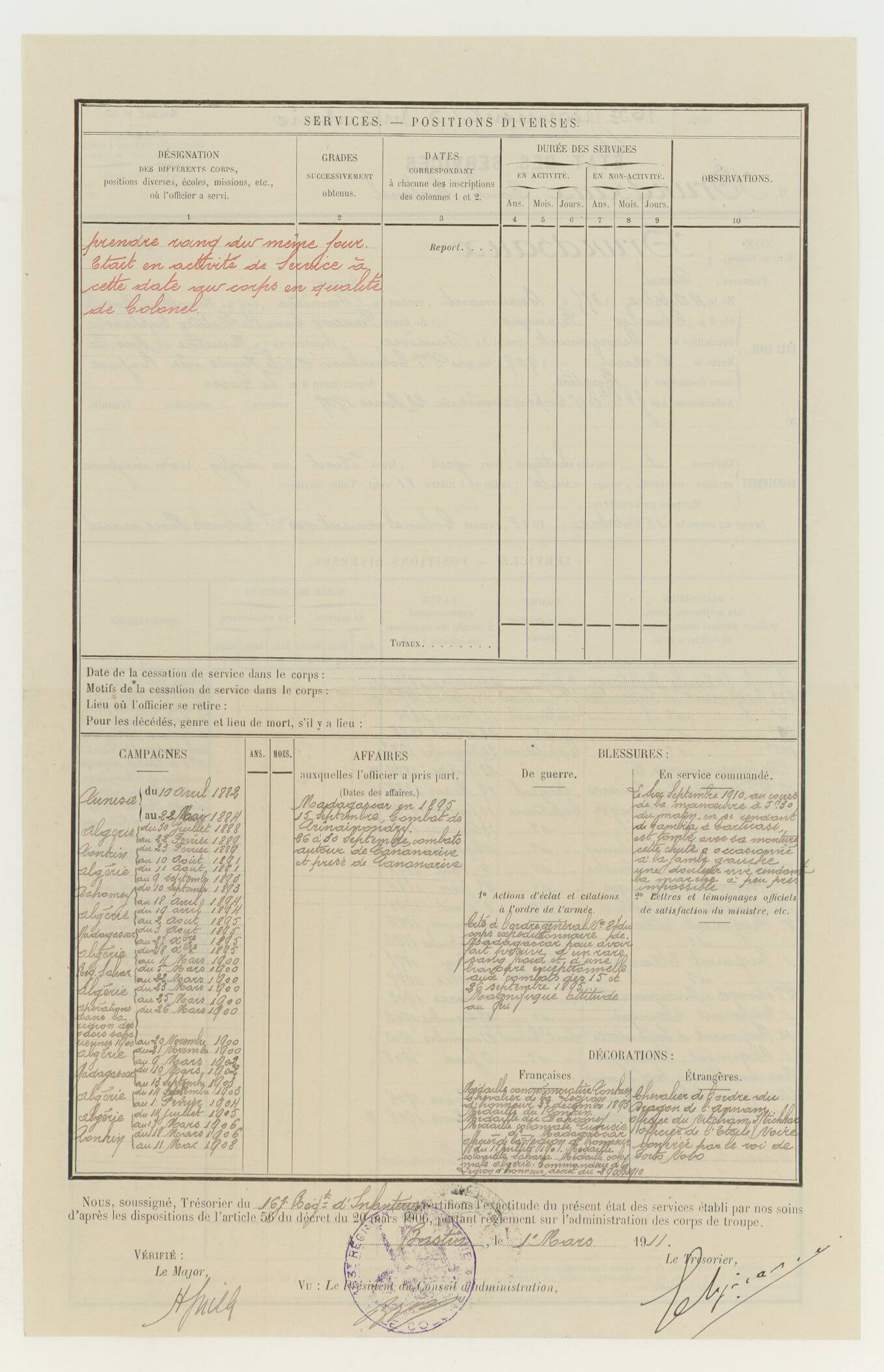

Paul Brundsaux’s service record included in his Légion d’honneur file:

- Tunisia, from April 10, 1882 to May 22, 1884

- Algeria, from July 30, 1888 to February 22, 1889

- Tonkin, from February 23, 1889 to August 10, 18

- Algeria, from August 11, 1891 to September 9, 1893

- Dahomey, from September 10, 1893 to April 18, 1894

- Algeria, from April 19, 1894 to August 2, 1895

- Madagascar, from August 3, 1895 to December 27, 1895

- Algeria, from December 28, 1895 to March 4, 1900

- Sahara region, from March 5, 1900 to March 22, 1900

- Algeria, from March 23, 1900 to March 25, 1900

- Operations in the region of the Saharan oases, from March 26, 1900 to November 20, 1900

- Algeria, from November 21, 1900 to March 9, 1902

- Madagascar, from March 10, 1902 to September 13, 1903

- Algeria, from September 14, 1903 to February 1, 1904

- Algeria, from July 14, 1905 to March 17, 1906

- Tonkin, from March 18, 1906 to May 11, 1908

Further readings

Porch, D. (1982): The Conquest of Morocco. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Porch, D. (1991): The French Foreign Legion. A Complete History of the Legendary Fighting Force. New York: Harper Collins Publisher.

Windrow, M. (2010): Our Friends Beneath the Sands. The Foreign Legion in France’s Colonial Conquests 1870-1935. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

“Un personnage hors du commun: l’une des quatre statuts du Monument aux morts de la Légion”, en www.legionetrangere.fr