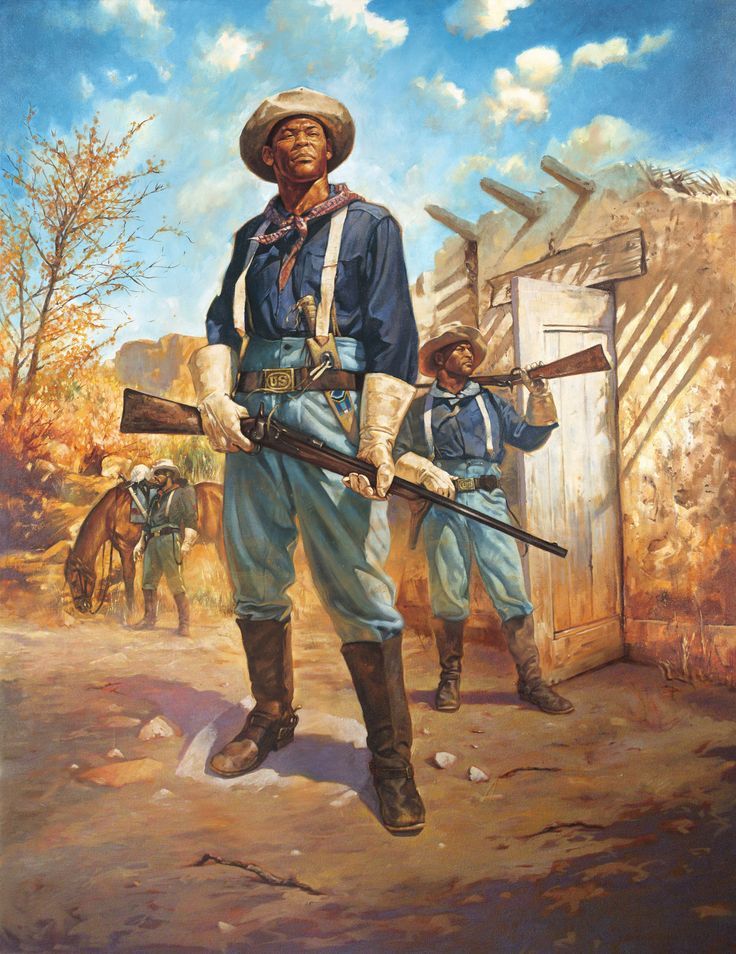

Buffalo Soldiers in the Spanish-American War 1898

Frank Jastrzembski

www.frankjastrzembski.com

‘Always in the vanguard of civilization and in contact with the most warlike and savage Indians of the Plains, the officers and men [of the Buffalo Soldiers] have cheerfully endured many hardships and privations, and in the midst of great dangers steadfastly maintained a most gallant and zealous devotion to duty, and they may well be proud of the record made, and rest assured that the hard work undergone in the accomplishment of such important and valuable service to their country is well understood and appreciated, and that it cannot fail, sooner or later, to meet with due recognition and reward.’

Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, Tenth Cavalry

Black soldiers have made an impact on the battlefield from the moment they were enlisted in the United States Army. President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for the recruitment of blacks in the army when it freed millions from slavery. Depleted from three years of war, Lincoln’s administration enlisted them to help replenish the manpower of the Union armies.

Many white officers were reluctant, even appalled, at the thought of commanding black soldiers in battle or to allow them to bear arms. Some cautioned they would make pitiful soldiers. These critics couldn’t have been more wrong.

Roughly 180,000 men donned the Union blue during the war. Black units gained renown for their heroism and devotion in battles such as Fort Wagner, Petersburg, and Nashville. Had these men not been enlisted to bolster the Union war effort, it is not unreasonable to think that the war could have dragged on longer than 1865.

Their prowess, discipline, and devotion during the American Civil War led to Congress sanctioning the creation of six black units in 1866 – the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments, and the Thirty-Eighth, Thirty-Ninth, Fortieth and Forty-First Infantry Regiments. By November 1869, the four infantry regiments were consolidated into two and renamed the Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiments. Despite the excellent Civil War record of black soldiers, some white officers who stayed on in the U.S. Army retained their prejudices and were dismayed at the thought of accepting senior positions in black regiments. Others who had witnessed their excellent service during the Civil War, like Benjamin H. Grierson, rushed at the opportunity to serve in these new regiments.

The four black regiments served in the western and southwestern United States over a period of thirty years. They were engaged on the frontier against the Apache, Cheyenne, Arapaho and Comanche tribes. Armed with inferior equipment and weaponry compared to white units, the black units earned the admiration of their superiors for their hard fighting, resilience, and loyalty. A ten-year veteran lieutenant colonel of the Ninth Cavalry, Wesley Merritt, proclaimed that, ‘I have always found the colored race represented in the army obedient, intelligent and zealous in the discharge of duty, brave in battle, easily disciplined, and most efficient in the care of their horses, arms and equipments.’

The Battle of the Saline River showcased the excellent qualities of the black cavalryman. In August 1867, Company F, Tenth Cavalry, beat off a series of attacks by 400 Cheyenne warriors for eight hours. The cavalrymen’s bravery and discipline became legendary for similar feats. Their Native American enemies bestowed on the seasoned regiments the nickname of “Buffalo Soldiers.”

Buffalo Soldiers in Cuba

All four veteran black regiments took part in the American invasion of Cuba in 1898. The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments were organized in the same division alongside white units under the overall command of the 61-year-old Major General Joseph Wheeler. “Fighting Joe” Wheeler had served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Now the Georgian found himself leading two crack black cavalry regiments into battle.

General William Shafter’s V Corps (17,000 men) landed at Daiquiri on June 22, advancing inland toward Santiago. The Tenth Cavalry served in the same brigade as two other regiments, both white, the First United States Volunteer Cavalry (Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders”) and the First Cavalry Regiment (Regulars). Wheeler rashly ordered his men to attack General Antero Rubín’s retiring units at Las Guásimas on June 24. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders stumbled through the thick jungle and collided with Rubín’s rearguard. Pinned down by heavy Mauser fire, companies of the First and Tenth Regiments came to the rescue, opening ‘a disastrous enfilading fire’ upon the Spanish left flank. The battle ended in a draw, but the Buffalo soldiers helped to rectify Wheeler’s sloppy attack.

The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments again saw action at the Battle of San Juan Hill on 1 July. The men of the Tenth Cavalry were awakened at daybreak from their camp near the hacienda of El Pozo and ordered to move out. They advanced down a road from El Pozo and arrived at the crossing of the San Juan River awaiting orders to assault the Spanish position at Kettle Hill. They remained exposed along the banks of the river while under Spanish artillery and Mauser fire. Despite remaining idle under a spray of bullets and shrapnel, First Lieutenant John J. Pershing of the Tenth Cavalry (later the commander of the American Expeditionary Force during the First World War) recalled that the cavalrymen acted, ‘as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees.’

The greyed General Wheeler rushed up to Pershing and gave him orders to advance on the Spanish position at Kettle Hill. The Tenth Cavalry was sandwiched between the First Cavalry on their left flank and the Rough Riders on their right flank. The “Smoked Yankees” – as they became known to the Spanish, according to Colonel Roosevelt – moved forward and hurried through the tall grass, crawled under barbed-wire fences, and hopped over wire entanglements while under a deadly barrage of Spanish fire to reach the crest of the hill. Wheeler’s six cavalry regiments (Lined up in this order from left to right: Third, Sixth, Ninth, First, Tenth, and Rough Riders) intermixed in the successful charge up Kettle Hill. Pershing admired how during the charge these men fought together, ‘unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by an ex-Confederate or not, and mindful only of their common duty as Americans.’ The Spanish soldiers retreated from Kettle Hill to their second, and stronger, position on San Juan Hill.

Wheeler’s cavalrymen next targeted the San Juan Heights. The mixed American units surged down Kettle Hill into an exposed valley before ascending and assaulting the second Spanish defensive position. The Spanish soldiers offered stiff resistance, but the momentum was on the side of the Americans, who wrestled San Juan Hill from their control. Sergeant George Berry of the Tenth Cavalry planted both the colors of his regiment and that of the Third Cavalry (picking it up after the white standard-bearer fell wounded) on top of San Juan Hill.

The Tenth Cavalry suffered the loss of half its officers (eleven of twenty-two) and twenty percent of its men in the American victory. When speaking of their role at San Juan Hill, Colonel Roosevelt afterward declared that ‘I don’t think any rough rider will ever forget the tie that binds us to the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry.’

Buffalo soldiers continued to serve with distinction during the Philippine-American War, First World War, and Second World War. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman ordered the United States Army desegregated. Whites and blacks would no longer be separated by units. The legacy of the Buffalo soldiers lives on, and as Grierson amply put, these men have earned their well-deserved ‘due recognition and reward.’

Further reading

Cozzens, Peter. La tierra llora. La amarga historia de las Guerras Indias por la Conquista del Oeste. Madrid: Desperta Ferro Ediciones, 2017.

Dobak, William A. and Thomas D. Phillips. The Black Regulars, 1866-1898. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Foner, Jack D. Blacks and the Military in American History: A New Perspective. New York: Praeger, 1974.

Gerstle, Gary. American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Glasrud, Bruce A., ed. Brothers to the Buffalo Soldiers: Perspectives on the African American Militia and Volunteers, 1865-1917. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011.

Leckie, William H. and Shirley A. Leckie. Unlikely Warriors: General Benjamin H. Grierson and His Family. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984.

MacAdam, George. “The Life of General Pershing.” World’s Work 37 (February 1919): 681-697.

O’Connor, Richard. “‘Black Jack’ Of The 10th.” American Heritage 18, no. 2 (February 1967). http://www.americanheritage.com/content/%E2%80%9Cblack-jack%E2%80%9D-10th.

Roosevelt, Theodore. “The Rough Riders: The Cavalry at Santiago.” Scribner’s Magazine 25, no. 4 (April 1899): 420-440.

Steward, Theophilus G. Buffalo Soldiers: The Colored Regulars in the United States Army. Amherst, N.Y.: Humanity Books, 2003.

Trask, David F. The War with Spain in 1898. New York: Macmillan, 1981.

VV. AA. Cuba 1898. Desperta Ferro Historia Contemporánea n.º 21, Madrid: Desperta Ferro Ediciones, 2016.