The French Conquest of Morocco

Douglas Porch

Author of The Conquest of Morocco and The French Foreign Legion

At the best of times, Morocco would prove a difficult country to master. The land was vast, much of it mountain or semi-desert, all of it remote. Its inhabitants were fiercely independent, although as elsewhere, opposition to French encroachment would prove spasmodic and transient. But aspiring European conquerors also faced constraints. Like most colonial affairs, the conquest of Morocco was incremental, and depended on an auspicious international environment, political alignments in Paris, and financing. Ardent European colonialists sought to convey an image of Morocco as failed state –a country so impoverished, its people so brutalized by an oppressive government that they yearned for rescue by the civilizing hand of Europe. In fact, the only reason that Moroccan independence had survived into the first decade of the twentieth century was that the European nations remained at cross purposes over who was to occupy the strategically important shoulder of Africa.

Morocco on the European diplomatic board

That began to change on 8 April 1904, when Britain and France signed what became celebrated as l’Entente cordiale. The agreement contained many codicils, one of which was the recognition of a Spanish zone of influence in Northern Morocco. However, the core principle was that London would no longer oppose France’s encroachments into Morocco, in return for a free hand for the British in Egypt. However, because Berlin had not been consulted, on the morning of 31 March 1905, the German liner Hamburg anchored off Tangier. On board was Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was conveyed on a horse through the tortuous labyrinth of Tangier’s narrow, trash-strewn streets to the German legation, where he uttered a few remarks about respecting German interests in Morocco. He promptly returned to the Hamburg and sailed away. The next day, the German consul in Tangier and future foreign minister of the Second Reich, Richard von Kuhlmann, announced that the Kaiser’s visit had been intended to underscore Germany’s commitment to Morocco’s continued independence.

The implications of this diplomatic standoff were significant, beginning with the fact that that Paris feared that an invasion of Morocco might provoke a hostile German reaction – indeed, in 1905 and 1911, French encroachments into Morocco would bring Berlin and Paris to the very brink of war.

Lyautey’s strategy for the conquest of Morocco

Aware of Morocco’s precarious political status, the French adopted a cautious multi-pronged strategy of encroachment. General Humber Lyautey, French commander of the Sud Oranais, the Algerian territory that bordered Eastern Morocco, nibbled at eastern Morocco, moving forward by stealth from Algeria to occupy sites within the territory claimed, but not occupied by the Sultan, giving the newly secured towns and villages French names to make journalists, diplomats and politicians, unfamiliar with the geography of Eastern Morocco, believe that they were part of French Algeria. Otherwise, the French converted crises, many of them provoked by swelling indigenous opposition to European encroachment, into strategic gains.

“In Morocco. Casablanca: eight Europeans, including five French, massacred by Moroccan tribes”, Le Petit Parisien no. 967, August 1907. Various issues such as the notorious Perdicaris Incident starring by El Raisuni in 1904, the Casablanca massacre of 1907 or the murder of doctor Mauchamp in Marrakech also that same year would be arguments put forward by France to justify the conquest of Morocco given the ungovernability of the country.

For instance, in 1907, the French placed a large force in Casablanca after Europeans had been massacred there, and pursued the conquest of the Chaouia, the hinterland behind the city. Moroccan tribesmen mounted a briefly effective mobile campaign against the French columns sent out from Casablanca. However, resistance largely collapsed in March 1908 after French General Albert d’Amade twice caught the resisters in their camps against which he brought the full power of French artillery and small arms.

A final French push into Morocco was precipitated in 1911 by a mutiny of the sultan’s askars (soldiers) against their French advisors in Fez. A French expedition launched to rescue the Europeans and the sultan besieged by his own troops touched off an international crisis which was only extinguished in November 1911, when Paris won the freedom to act in Morocco by conceding territory in the Cameron to Berlin. While the 1911 accord between France and Germany settled the Moroccan question on the diplomatic level, the French conquest remained a piecemeal affair, suspended by the outbreak of the Great War in Europe, and further disrupted by the Riff War (1921-1926). Only in 1934 did the remaining “dissident” tribes in Morocco submit to French rule.

“In Morocco, the column of General Baumgarten occupies Taza”, Le Petit Journal, May 1914. Source: Gallica. After the capture of Marrakesh in 1912, the French conquest of Morocco focused on the north, against the Berber Zaian confederation, a campaign that was hampered by the outbreak of the First World War, and that would last until 1921.

Morocco ca. 1900. A country because the sultan says so

The problem for indigenous resistance was that Morocco’s sense of a unified political and cultural community was weak. Although nominally unified, Morocco was little more than a geographical expression of rival tribes and families and competing economic interests whose interactions were moderated by the Sultan. Morocco in 1900 was a country because the Sultan said it was, although he exercised only nominal control over it. The mountains divide the country culturally into Arab and Berber, a mainly linguistic and cultural distinction. Europeans generally despised Arab town dwellers whose cultural center was Fez with its famous university and corps of religious scholars, known as the ulama, as indolent, duplicitous, cowardly and decidedly anti-modern. In contrast, the Berber populations of Marrakech, the Atlas Mountains and the Riff, who made up roughly 60 per cent of Morocco’s estimated population of five million at the turn of the twentieth century, were admired as warriors for whom bravery in battle was de rigueur.

The government of Morocco was called the makhzan, which means “storehouse” or “treasury.” But Morocco had no “capital” as European understood the term. The Sultan, surrounded by his viziers (ministers), his harem, his soldiers (askars) and a small city of camp followers, that included scribes and merchants that might number thirty thousand souls, meandered between Fez, Meknes, Rabat and Marrakech, depending on the political situation. As King of Morocco, the Sultan was able to impose his rule on those portions of his empire that his army could control – essentially the fertile crescent to the west of the Atlas. Elsewhere, his temporal authority was for practical purposes ignored.

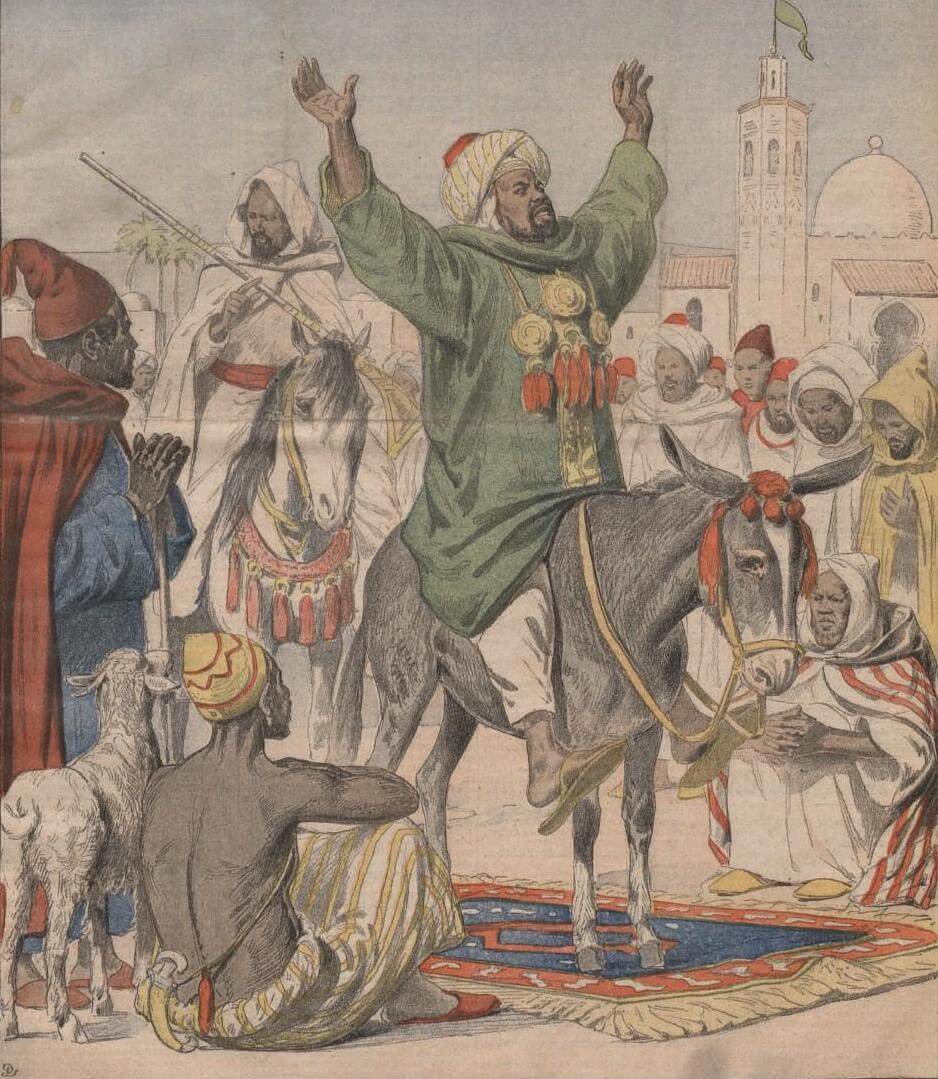

“Agitation in Morocco”, Le Petit Journal no. 627, November 1902. The fragile reign of the dissolute Abd-al Aziz (r. 1894-1908) was constantly convulsed by a succession of characters who undermined the always called into question central power, from ambitious and reckless warlords like El Raisuni in Tangiers or al-Hibba in the south, to pretenders like his brother Mulay Hafid (who will rise up against him and succeed him to the throne) or a character as unlikely as El Rogui, who claimed the throne by pretending to be the firstborn of Hassan I (both were one-eyed). Also known as Bou Hamara (“the one with the donkey”), for five years this obscure character of humble origins will rule northern Morocco, where he will grant mining licenses to French and Spanish companies.

What gave Morocco an ephemeral identity was that, as a descendant of the Prophet and Commander of the Faithful, the Sultan was accorded great veneration. Even those areas of the land that refused to pay his taxes or garrison his troops, regarded him as their caliph and custodian of the Dar al Islam –the House of Islam. The Moroccans had a name for those territories whose inhabitants lived in this curious relationship with their government: bled el-siba, or “land of dissidence.”

Although some European colonialists promoted Morocco as the “California of Africa,” for Europe, Morocco had only one value – strategic. Ironically, this had prolonged Morocco’s independence as most of the remainder of Africa had been digested by European imperialists. But as disputes among Europeans over who was to control Morocco solidified divisions in Europe in the run-up to the Great War, so too the pressure of modernization divided Moroccans into two opposing camps: one made up of those who believed in isolation and tradition as the best defense against encroachment from Europe, and the other which argued that a reformed, Westernized, and consequently strengthened government might better protect the country’s independence.

“In Fez. A solemn audience with the Sultan of Morocco. M. Saint-René Taillandier exposes, before the sultan, the program of reforms proposed by France”, Le Petit Journal no. 752, April 1905. Some reforms that, of course, were not cheap and involved the granting by French banks of important loans in exchange for abusive conditions, whose ultimate goal was to cause further internal instability that would lead to the conquest of Morocco.

Unfortunately, reform proved particularly destructive when applied in a Moroccan context. Loans from French banks for infrastructure improvements from 1901 increasingly drove the Makhzen into debt, strengthened European control over the economy, and soon discredited the Sultan in the eyes of traditionalist ulama of Fez and the religious brotherhoods or zaouia, jealous of their lands and privileges, and suspicious of change tainted with Christianity. Likewise, merchants, caids, soldiers and customs officials were reluctant to replace the bribes and extortion by which they lived with fixed contracts or a modest government salary. The transformation of the Sultan’s askars into a modern army that lived in barracks instead of cohabiting with their women in the rambling neighborhoods near the Sultan’s various palaces was especially objectionable and, as seen, had sparked a military mutiny in 1911.

The impact of rapid industrialization of warfare in Europe in the late nineteenth century soon had repercussions for Moroccan societies that lacked the ability to adapt to the challenge of Western military encroachment. Rather than stiffen potential Moroccan resistance, the introduction of modern arms which had become a torrent in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, had empowered minor chiefs with private access to arms merchants, which allowed them to challenge central authority, and so accelerated Morocco’s social and political disintegration.

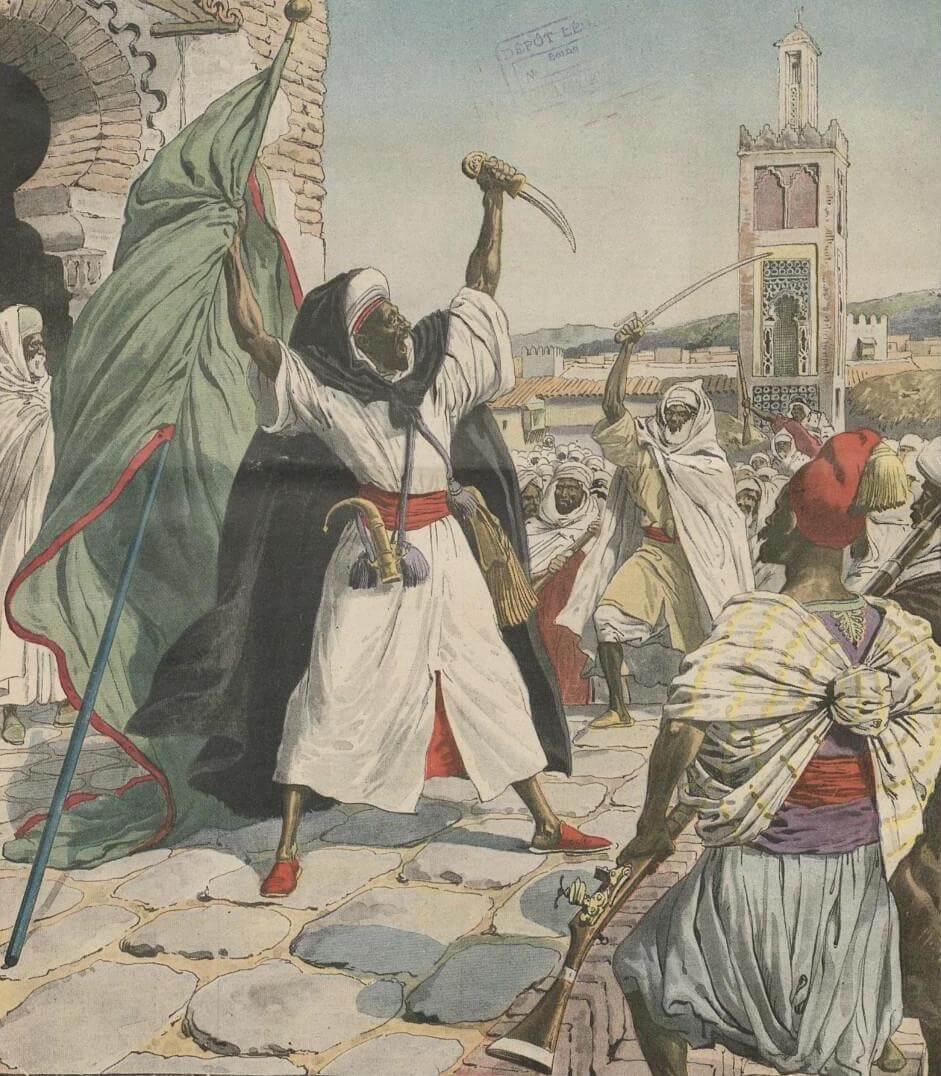

“In the Moroccan South. Hibba Partisans Call to Arms”, Le Petit Journal no. 1137, September 1912. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Ahmed al-Hiba led a powerful armed resistance in 1912 against the French conquest in southern Morocco, during which he managed to take Marrakesh, where he proclaimed himself sultan. Despite his defeat at the battle of Sidi Bou Othman in September of the same year, he would continue the fight until his death in 1919.

In these conditions, modernization undermined Morocco’s ability to stand toe-to-toe with Western armies. Individually, Moroccan Berbers in particular made excellent soldiers, and later became highly prized recruits by France’s armée d’Afrique. In Moroccan culture, battle played out as theater where the individual warrior sought glory through a display of personal courage as well as plunder. It was not, in a Clausewitzian sense, “politics by other means.” Indigenous forces had primitive logistical systems, so that they quickly ran out of ammunition and food after a few days and were forced to disperse. Technology was fed into existing tactical habits, which were often anchored in social organization and political precedence, which could not be adjusted without altering the political order. So, acquiring technology often proved a mixed blessing, especially in Morocco which lacked a national structure to make it efficient.

The fissiparous nature of Moroccan society made it difficult to cobble together a common resistance. Moroccans were not uniformly hostile to the invader, nor did they have a sense of fighting a war of national survival. Divided by geography, language, rivalries of caste, tribe, clan or family, their bonds of common culture weak, a unified response based on a shared sense of national self-interest, when it could be mustered, seldom survived the first military debacle. Each group or clan must decide whether it was in its interests to fight or make peace. Few resistance leaders were “bitter-enders.” In the 1920s, a clever leader like Abd el-Krim in the Riff was able to combine geography and insurgency tactics with a lack of fighting spirit of many Spanish soldiers, to create a short-lived independent Republic of the Riff. Elsewhere, however, brave men fought openly, offered their breasts to bullets. Victory won by stealth was dishonorable. Thus, after a display of resistance, most Moroccan leaders were forced to seek accommodation with the colonial invaders.

“In Morocco. General Lyautey receives the submission of a rebellious tribe and the return of stolen arms,” in Le Petit Parisien, July 1906. Springfields, Remingtons, Chassepots… Morocco was a prime destination for arms from fire that had become obsolete in the West, which flooded the black market. “You do not know what a gun means to an Arab; it is his son, and his master,” said El Raisuni, who despite his cunning was once caught under the guise of delivering him a modern rifle.

Realizing the fissiparous nature of indigenous societies, the French had early on created an organization to provide intelligence on, divide, and eventually control conquered lands in North Africa. Created in the early days of the French conquest of Algeria in 1833, the bureaux arabes were part tribal outreach corps, administrative organization, police force, and intelligence service meant to study North African society, reveal its seams and weaknesses, and identify potential collaborators. Incorporating indigenous levies into an expeditionary army gave the French a political and psychological advantage and helped further to fracture a unified Moroccan response to invasion. At the turn of the century, Lyautey developed this combination of intelligence collection and economic incentive, backed by the threat of punishment, into a technique of conquest, which he labeled “peaceful penetration” –in effect, a method of “soft colonialism” that sold better in France than it actually worked on the ground in Morocco, and whose limitations were exposed by Abd el-Krim.

Further readings

Porch, D. (1982): The Conquest of Morocco. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Porch, D. (1991): The French Foreign Legion. A Complete History of the Legendary Fighting Force. New York: Harper Collins Publisher.